Edwardian Buxton

The Edwardian town that Robert and brother John were born into was identifiably the town we see today. The population of Buxton has almost doubled over the last century – from around 11,500 when Robert was born to today’s 22,200. That growth has taken place on the fringes of the town – the centre of which is little changed.

Frank Matcham’s Opera House, the last of the major buildings in the heart of the town, dates from 1903, two years before Robert was born.

St. John’s Church, the Pavilion Gardens, the Devonshire Hospital, the Palace Hotel and the twin railways stations were all well-established landmarks and would have been familiar to the Stevensons. Buxton, at the beginning of the 20th century, had developed on land most of which was owned or managed by the Duke of Devonshire’s Estate. The Estate derived a steady income from the Mineral Water Baths up until their sale to the town in 1904.

King Edward VII visited the town in January 1905 – two months before Robert was born – the first known visit to Buxton by a ruling monarch. As the town’s historian Mike Langham noted, “The chief purpose of the visit was to inspect the renowned Devonshire Hospital and Buxton Bath Charity…

“By 1905 Buxton had reached its peak. The health resort had much to look forward to. The services and utilities were in place, up-to-date and working effectively. The growth up to 1905 had provided apartments and lodging houses in all parts of the town serving all classes of visitor and an extensive range of hotels and hydros. The Empire Hotel built in the Park between 1901 and 1903 is a perfect example of the commercial optimism and buoyancy of the town at the opening of the twentieth century…

“In 1905 the view from Solomon’s Temple was over a townscape laid out and built with optimism for the future. ‘Buxton has many advantages as a residential town. As a fashionable health resort it offers the attractions of first-class concerts and plays, excellent shops and well-kept streets, pleasant society and good schools, a fast train service and many of the advantages of a large city. On the other hand, the disadvantages of town life are absent, we have pure, bracing air, charming scenery, and delightful gardens, quietness and rest. In a word, the best features of city and country life are combined…’”.

In 1905 Buxton was as fashionable and as attractive a town as it would ever be. (Though the redevelopment of The Crescent as a 5* spa hotel may hold the key to Buxton becoming an international tourist destination). The town had “twenty-seven hotels and more than 300 lodging houses for a weekly influx of 4,000 visitors.” It is easy to imagine why Hugh Stevenson would move to Buxton as he began a second family. His business interests in Manchester were still close at hand and he had a clean, modern town in which to live.

Robert’s early life

Robert Edward Stevenson was born on 31st March 1905 at Devonshire House, Corbar Road, Buxton. This maternity centre survived until the 1980s.

His brother John Stanley was also born there in 1907. Their father was Hugh Hunter Stevenson and mother was Clementina Louise; the family lived at “Rockwood”, 137 Park Road. Near neighbours would have been Vera Brittain and her family at “Melrose”, number 151.

Hugh was in his late 60s by the time Robert was born. His first wife, Jane, had seven children and died before the end of the 19th century. Hugh and Clementina (who was born in 1870) married in Somerset in 1903.

Hugh’s business interests – he owned a paper box-making company – were extensive and at the time of Robert’s birth he seemed settled in the north-west. However within a few years he opened a factory in south-west London and by 1911 the family was living at 22 Mansel Road, Wimbledon not far from the Summerstown factory.

This home, large and semi-detached did – like “Rockwood” – befit a well-established and successful businessman. In the Wimbledon home they employed a governess – for the two boys – and a young servant, Mabel Birchenall, who moved with the family from Buxton.

Mary Poppins was set in 1910 and we can only conjecture about how Robert’s own childhood and early home life might be reflected in that of the Banks family.

Robert’s father died in 1915 but even before then he was at boarding school. From September 1914 to July 1918 he was a pupil of the Observatory House School, Westgate-on-Sea, near Margate on the north-east Kent coast.

His education then continued at Shrewsbury School – one of England’s longest established independent public schools. He was at Shrewsbury – at that time an all-boys school – until July 1924 when he was 19.

By this time he was in the care of his mother who had remarried. According to the Cambridge University records Mrs Ina Cottle was the wife of Captain AJ Cottle, Royal Engineers and they lived at Cair Glon, Cam, Gloucestershire. Clementina Stevenson married Abram Cottle in 1919 and used Ina, a shortened version of her first name. She lived to be 89 before dying in Chichester in 1959.

We must suppose that Robert had a sufficiently robust personality to cope with this unsettled early life – though it would not have been so unusual for the child of a prosperous, middle-class family to be away from home for most of their school years.

Robert at Cambridge: 1924-1931

In any event Robert must have made the most of his opportunities at Shrewsbury because he was offered a scholarship place at St John’s College, Cambridge.

Robert studied Mechanical Sciences at St John’s College from 1924 and graduated with First Class Honours in 1927. He was awarded the John Bernard Seely Prize for Aeronautics in 1926. His tutor was the distinguished polar explorer and scientist JM Wordie.

He was President of the Cambridge University Liberal Club from 1926/1927 – succeeding Michael Ramsey who later became Archbishop of Canterbury. In 1926 he was vice-president of the College Debating Society and was second in a Reading Prize as well as winner of Wright’s Prize in Mechanical Sciences.

Stevenson remained at Cambridge to complete an MA in psychology which was awarded in 1931. His original intention was to write a thesis on the psychology of the ‘ki-ne-ma’ – a plan prompted by seeing his first film Sally, Irene and Mary starring Joan Crawford. This was screened in Britain in 1926 when Stevenson would have been 21. Apparently he loved the film and Crawford. He was not, though, steeped in film as some directors were.

In 1928 he edited Granta, the prestigious literary magazine and became President of the Cambridge Union Society.

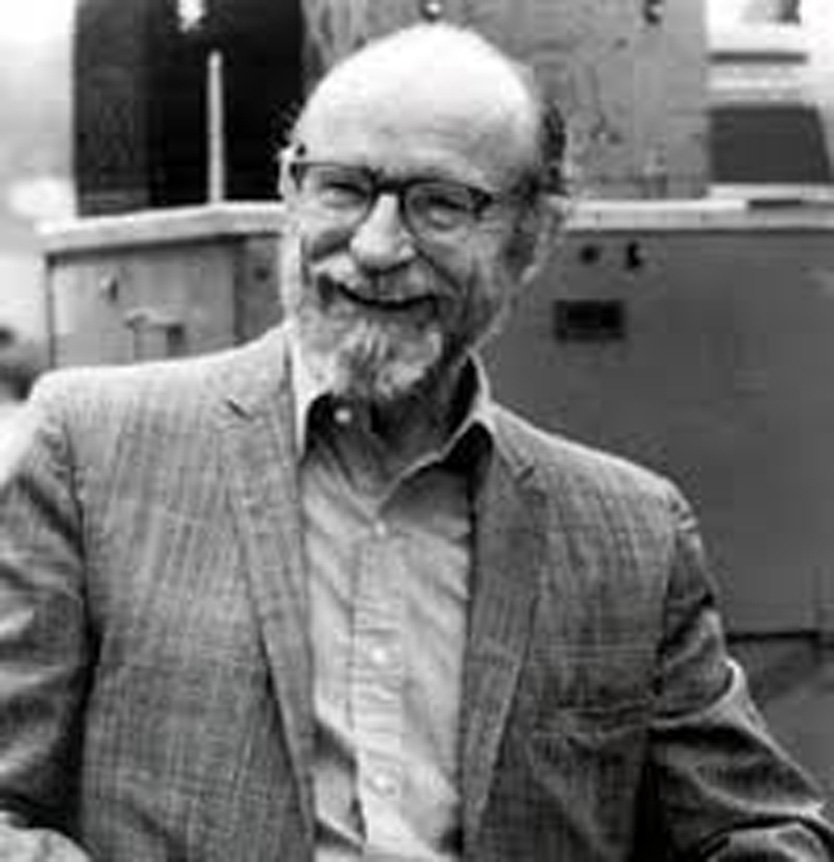

Stevenson was, evidently, an enthusiastic, all-round sportsman. The pictorial evidence suggests that he retained a lean, athletic frame and build throughout his life.

He played football and was a speedy right-winger – for the College 3rd XI in his first year. Though a report remarks pithily that his speed “would be of greater service if he could cultivate a stronger and more accurate centre.”

His athletics prowess was more remarkable. He won high jump and long jump events (21’ 1” being a good distance in the long jump) and was a member of a successful relay team.

It is clear that Robert had a broad view of education – embracing the physical sciences, psychology, literature, politics and sport. His interest in film and cinema only became apparent in his MA studies and it was then that he made some tentative forays into the world of film-making though initially as a writer rather than any of the technical aspects of the business. In 1928 he was part of the writing team for Balaclava a silent film about the Charge of the Light Brigade – a Gainsborough Picture produced by Michael Balcon.

Robert worked for Gainsborough, alongside completing his MA, reading scripts before becoming a screenwriter in 1929.

Robert’s apprenticeship in film with Gainsborough

Michael Balcon co-founded Gainsborough Pictures in 1924 and took over studios in Islington, north London. Balcon went on to be associated with the singularly British Ealing studio

films but he had an internationalist outlook. His parents were Jewish immigrants and Balcon learned much from German film-makers in the 1920s. It was his view that British films had to aspire to compete with the best – and at that time the best were the American and German industries.

Balcon had visited the huge Ufa (Universum Film Aktiengesellscaft) Studios in 1924 and met Erich Pommer who managed an operation producing up to 50 films a year with significant directors such as Lang, Murnau, Pabst and Wiene.

Gainsborough and Ufa co-produced The Blackguard in Germany in 1925. The young Alfred Hitchcock served his apprenticeship with Gainsborough – writing the screenplay and designing the sets for The Blackguard and learning much from the techniques of German productions.

In 1930 Stevenson co-wrote Greek Street – a musical, directed by Sinclair Hill. (Gerard Arthur Lewin Sinclair Hill later served in the RAF and was a Wing-Commander. In one of life’s curious coincidences, he died near Buxton in March 1945 following a plane crash whilst on military service!)

Over the next five years Stevenson developed his knowledge and skills in the craft of film making in France and Germany as well as England. In 1932 Stevenson was working at Ufa under the supervision of Pommer on Happy Ever After. French, German and English versions of the film were shot concurrently. Stevenson was the only Briton supervising English language versions and he observed that given the English versions were filmed after the German and French takes it was hardly surprising if the crews were bored at that stage and the English takes were a little hurried. (In November 1933 Stevenson delivered a lecture to the British Kinematograph Society on his experiences of German and French studios. He found the Germans to be organised and efficient, the French were more casual in their work but individual flair and genius triumphed. Some stereotypes are hard to shake off!) Robert also noted how language and culture made the same scenes and films appear quite different to audiences in Germany, France and Britain. German narrative pace was too slow for British viewers and “in questions of sex, the Continental story often appears to the English public brutal and ill-mannered, and the romantic lover, whom the Continentals consider a hero, often appears to an English audience a cad”. Stevenson also wrote at length about the problems in translating the German scripts into English (how to deal with puns and other humorous elements) and the diplomatic difficulties to be dealt with when it came to giving names and nationalities to villains.

Stevenson worked on a couple of breezy comedies with Jack Hulbert – a popular singer, dancer and comedian. The Camels Are Coming, Falling for You and Jack of All Trades are very much Hulbert vehicles but allowed Robert to show himself to be a safe pair of hands. He seems to have been a restraining influence in these films and the story-telling, such as it is, is managed deftly and briskly.

Balcon evidently had a high regard for Stevenson and by 1936 he was judged ready to direct his first film.

Tudor Rose – 1936

Tudor Rose tells the story of Lady Jane Grey and was, for its time, a lavish and costly production and established Stevenson as a director of skill – though not all cared for the film. Here is Graham Greene’s less-than-enthusiastic review published in The Spectator 8 May 1936.

“Tudor Rose is one of the more distressing products of the British screen: the fault is not in the director, who has made a smooth, competent if rather banal, picture, but in the vulgarity of the scenario. The story of Lady Jane Grey is surely dramatic enough to be converted truthfully into film material, but this sentimental pageant in fancy-dress could have displayed no more ignorance of the period if it had been made in Hollywood. There is not a character, not an incident in which history has not been altered for the cheapest reasons. Edward VI is shown as a preparatory schoolboy who wants to get out and play with a gun: the weakling Lord Guildford Dudley becomes a tender and romantic ‘boy husband’: Lady Jane Grey herself, perhaps the nearest approach to a saint the Anglican church has produced and a scholar of the finest promise, is transformed into an immature child construing – incorrectly – Caesar’s Gallic War and glad to be released from tiresome lessons. This, I suppose, is the Dark Age of scholarship and civilization, and one ought not to expect anything better from celluloid artists than this sneering attitude to the learning of the Renaissance. The dialogue in English films is notoriously bad, from Mr Wells downwards, but I have seldom listened to more inchoate rubbish than in Tudor Rose. The style chops and changes; sometimes, when the Earl of Warwick (so the Duke of Northumberland remains throughout this film) or the Protector Somerset is speaking, the dialogue is written in unconscious blank verse; at other times it consists of the kind of flat simplified colloquialisms that Mrs Naomi Mitchison has made popular in historical novels.”

Unsurprisingly Stevenson robustly disputed Greene’s assertions. More recent critics are altogether kinder in assessing where Tudor Rose belongs in terms of English film history. Jeffrey Richards (2010) has this to say: “One of the most impressive historical films made on the subject of the British monarchy… It opted for a simplified but lucid and forceful exposition of the reign of King Edward VI…

“The film, besides endorsing legitimism and opposing all attempts to set aside the lawfully ordained succession, sets up a strong contrast between the crown as a symbol of national unity and order and the self-seeking of aristocratic faction… Private lives and private desire count for nothing when it comes to the national interest.”

King Solomon’s Mines with Paul Robeson

In 1937 Stevenson filmed a very different literary adaptation. H Rider Haggard’s novel King Solomon’s Mines was hugely popular and the cast included Paul Robeson, John Loder (again) and Cedric Hardwicke as the hero, Allan Quatermain. Once again, Graham Greene felt let down. Here is his review published in Night and Day, 12 August 1937:

“King Solomon’s Mines must be a disappointment to anyone who like myself values Haggard’s book a good deal higher than Treasure Island. Many of the famous characters are sadly translated. It remains a period tale, but where is Sir Henry Curtis’s great golden beard (into which, it will be remembered, he muttered mysteriously ‘fortunate’ when he first met Allan Quatermain)? Mr Loder’s desert stubble is a poor substitute. Umbopa has become a stout professional singer (Mr Robeson in fact) with a repertoire of sentimental lyrics, as un-African as his figure, written by Mr Eric Maschwitz. Worst crime of all to those of us who remember Quatermain’s boast – ‘I can safely say there is not a petticoat in the whole history’ – is the introduction of an Irish blonde who has somehow become the cause of the whole expedition and will finish as Lady Curtis (poor Ayesha).

“Yet it is a ‘seeable’ picture. Sir Cedric Hardwicke gives us the genuine Quatermain, and Mr Rolan Young, as far as the monocle and white legs are concerned, is Captain Good to the life, though I missed the false teeth, ‘of which he had two beautiful sets that, my own being none of the best, have often caused me to break the tenth commandment’ (what a good writer Haggard was). The one-eyed black king Twala is admirable, the direction of Mr Robert Stevenson well above the English average, the dovetailing of Mr Barkas’s African exteriors with the studio sets better than usual, but I look back with regret to the old silent picture which was faithful to Haggard’s story: I even seem to remember the golden beard.”

Seeing the film in at the Buxton Film Festival in 2017 it was hard not to conclude that the film effectively sanctions British colonial history. Paul Robeson’s biographer, Martin Baum Duberman, notes that on the film’s release the “black New York Amsterdam News expressed its gratitude that the Film ‘at least doesn’t reek with the imperialistic theory of British superiority’ (most viewers today find that reek palpable)…” Some critics see it as being essentially imperialist – giving permission in the years either side of the Second World War, so to speak, for continued British exploitation of the African continent and its peoples. Robeson had hoped to use his influence to get the film to say something more positive about the black experience and it may well be that he succeeded in toning it down – the ‘native’ savagery might have been even more brutal otherwise. Certainly the film does not question any aspect of the existence or purpose of the British Empire – which is presented essentially as a romantic, civilising adventure. The story-telling focuses on the quest for riches and profit to be extracted from Africa.

Marriage to Anna Lee

Robert married four times – the first three marriages ending in divorce. His second wife was the actress Anna Lee who has been described as “a sweet-faced, spirited blonde” but this shorthand implies a limited range; she was, in fact, versatile and she showed this in the five films that she worked on with Stevenson.

They married in 1934 and were together for almost ten years. For a while the couple lived at Cardinal’s Wharf, Bankside, London (in a beautiful house next to the modern day Globe Theatre) until soon after the outbreak of war when they moved to the States. They had two daughters. Venetia was born in London and Caroline after the move to the US. (Their home at 49 Bankside is the subject of an excellent book by Gillian Tindall, The House By the Thames).

In an interview given to Bob King for the magazine Films of the Golden Age (1997) Anna said: “(in 1934) we were filming in Egypt near the Suez Canal. We were making The Camels Are Coming and living in tents for about five weeks. All the crew were sick except me. Everything was going wrong with the production. Back in England they were getting nervous because no film was being sent back, so they sent Bob out as a troubleshooter.

“I was riding a pony in the desert one evening, and as I was coming back, there he was. He was dressed all in white, looking like a Noel Coward hero. All the other crew were sick with dysentery, and he looked so clean and healthy. I fell in love right there”.

The marriage ended after Stevenson began an affair with his secretary – though Anna quickly remarried. Lee remembered him fondly: “Bob was a very nice man, kind and gentle. He was a great mathematician, always working on complex problems no one else could solve.”

Stevenson also loved toy trains and had sets running around the house. Lee recalled: “Once he even cut a hole through my clothes closet so that he could run a track through. I complained bitterly about that.”

Stevenson and Lee worked on five films together after their marriage. The Man Who Changed His Mind (1936), King Solomon’s Mines, Non-Stop New York (both 1937), Young Man’s Fancy (1939), and Return to Yesterday (1940).

The couple’s first daughter Venetia was born in London in 1938. A noted beauty, she had a short career in film and television before marrying Don Everly in 1962.

Anna died in 2004, aged 91, in California.

Moving to Hollywood and his first American films

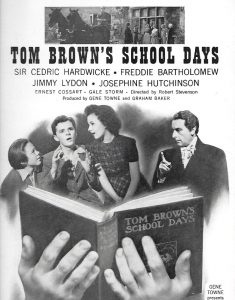

By the time Return to Yesterday was in British cinemas Stevenson and Lee had moved to the States and Robert was working on a version of Dr Thomas Arnold’s tale of British public school life – Tom Brown’s Schooldays. Stevenson has been described as a pacifist and some have said that was part of the reason for his leaving Britain – though it was also the case that he had been offered a contract by David O Selznick. His convictions about the war may have changed in time – certainly he was involved in some films that supported the Allies cause and he was pictured in American army uniform. In the event Robert made no films for Selznick but was loaned to a number of Hollywood studios over the course of 10 years or so.

But back to his first American film. Perhaps it was felt safer to a give a British director a story that he would feel comfortable with – this is not to suggest that Robert’s time at Shrewsbury was anything like the version of Rugby that Arnold gives us. The cast also included the very English Sir Cedric Hardwicke as Dr Arnold but most of the other actors were American.

In 1941 Stevenson directed Maureen Sullavan and Charles Boyer in what is generally regarded as the best version of Back Street – a story of young love thwarted. He made another half -a-dozen films – directing the likes of Jane Russell and Victor Mature (The Las Vegas Story), Ava Gardner and Robert Mitchum (My Forbidden Past), and Hedy Lamarr (Dishonored Lady).

Dishonored Lady (1946) was held up whilst the censors sought revisions: the Lamarr character was to have two affairs and “a night of sordid passion” which was judged to be “overloading”. The film noir To the Ends of the Earth (1948) dealt with opium smuggling into the States and at the time seemed unnecessarily violent.

The films he made for Howard Hughes from the late 40s – beginning with Walk Softly Stranger and The Woman on Pier 13 (aka I Married a Communist) probably are the low-point in Stevenson’s film career and may explain why he moved away from cinema for a period. They seem to be rather lazy films – in terms of plotting and script – relying on the glamour of the stars to attract audiences. Most of these films lost substantial amounts at the US box office.

From 1952-1957 he worked largely in TV, including on series such as Gunsmoke, Alfred Hitchcock Presents and Zorro before returning to film with Walt Disney and completing a body of work that secured his reputation as a director.

Jane Eyre and Orson Welles (1943)

Come 1943 Robert was involved in what proved to be one of the high-points in a long career. Orson Welles had already completed Citizen Kane and The Magnificent Ambersons but he was not a critical or commercial success at that time. Welles was a forceful and single-minded creative genius; Stevenson was shy, quiet but determined to work in his own way. Evidently in their collaboration on Jane Eyre they found a way of working so that both were satisfied with the outcome. Welles is on record as saying: ‘I did a lot more than a producer ought to, but Stevenson didn’t mind that. And I don’t want to take credit away from him, all of which he deserves.’ Joan Fontaine – who witheringly described Welles as ‘the boy genius’ – wrote of the ‘slight, timid, gentlemanly Robert Stevenson’ and how, having been ‘demoted to director-in-name-only’ he gradually regained control: partly because Welles’ time and energy was being consumed by a passionate affair.

This was the sixth attempt to make a film out of Charlotte Bronte’s story in a period of just 30 years – such was the fascination and cinematic potential of the story.

Aldous Huxley had a hand in the script and the cast includes an uncredited Elizabeth Taylor who plays Jane’s consumptive young friend Helen. There are plenty of gothic touches – mist, storms, deep shadows and the like – even though the filming took place almost entirely in an American studio. Bernard Herrmann contributes a suitably stirring score but the film belongs to Joan Fontaine (Jane) and Welles (Mr Rochester). Even now this film – first shown in the UK in 1943 – is regarded as one of the very best Brontë adaptations.

It was an expensive production – in part because Welles was paid so much – and the novel had to be heavily edited to get the film down to 95 minutes running time. The design and production of the film are required to help with the story-telling and conveying the mood and sense of place. Academic Michael Riley explains how some of the early scenes work: ‘…the film opens with an eerie shot of a burning candle moving through a darkened hall at

Gateshead until the figures of Bessie and a footman are revealed. The two servants fetch the child Jane from a dark, locked room and take her to the drawing room where her aunt and Mr Brocklehurst await her. Shots from both low and high camera angles suggest on the one hand Jane’s view of an adult world which looms oppressively above her and on the other the adult point-of-view which sees only the child’s small stature and insignificant appearance. And shots which often picture Jane alone convey the isolation which the novel describes…

‘Cinematically the darkness of Jane’s confinement in the opening scene is juxtaposed to the brightly lighted comfort of her aunt’s drawing room. This proves to be an important element in the film’s visual design… Throughout the film there is a movement from darkness towards the natural light.’

Stevenson’s contribution to the war effort

Some have suggested that Stevenson went to the States because of his pacifist views, yet he became an American citizen in 1940 and worked for the US War Department from 1942 as a producer. He served as a captain until 1946 – spending time on the Italian front. He worked with Frank Capra on a 40-minute propaganda documentary Know Your Ally, Britain.

He also directed Joan of Paris, released in 1942 – a story of the French resistance – which was nominated for an Oscar for the music written by Roy Webb. The film was completed in 1941 but release was held up until after the attacks on Pearl Harbor which meant that audiences were generally more sympathetic. The strong cast also helped: stars Paul Henreid and Michele Morgan not only toured the States promoting the film, they also promoted investment in war bonds.

Apart from that Robert worked with dozens in the Hollywood film industry on Forever and a Day. One of Hitchcock’s biographers provides an insight:

‘Shortly after the war broke out, a small group of British expatriates in Hollywood began to meet to devise ways to confront American neutrality and promote England’s cause. Congregating regularly at the office of Cecil B De Mille, this group felt obliged to keep its existence secret, not only because the Neutrality Act made pro-war agitation illegal, but because of the political tensions within the film industry. Hollywood mirrored America with its split between citizens anxious to join the fight against Hitler and those – a peculiar alliance of America Firsters and Communists abiding by the Hitler-Stalin pact – who preached isolationism.

‘For two years, this small expatriate group would operate as a virtual cell of British intelligence, with the goal of nudging America toward involvement in the war. Its key figures included actors Boris Karloff (whose brother John Pratt was in the London office of MI6) and Reginald Gardiner, directors Robert Stevenson and Victor Saville, and Charles Bennett. Either Bennett or Saville, the group’s informal leader, brought Hitchcock to meetings…

‘Hitchcock joined Saville, Cedric Hardwicke, and Herbert Wilcox in sending out a general call to British natives in Hollywood. Actors, writers, and directors were asked to show their patriotism by donating their services to an anthology picture whose earnings would be pledged to war-related causes.

‘Pledges of support were quickly received from Ronald Coleman, Errol Flynn, Charles Laughton, Vivien Leigh, Laurence Olivier, Herbert Marshall, Ray Milland, Basil Rathbone, George Sanders, Merle Oberon, and many others. Hitchcock was named to the Board of Governors of Charitable Productions producing the anthology film and distributing its proceeds. He also agreed to direct one of the five segments. The proposed story of Forever and a Day, as the picture was to be called, would follow two families, masters and servants, living in a London house over the course of thirty years (1899-1929).’

Sir Cedric Hardwicke, in his memoir, offers a slightly different perspective:

‘Almost without exception, the producers of films started out as the exploiters of an entertainment novelty. Though their baby had grown to a giant, they persisted in the methods of their early, hungry years, milking the box office for every cent it would yield, taking the profits out, accepting no responsibility for providing either culture or cash in return.

‘At least, in this war situation, I considered, profits should not be the ultimate and exclusive motive of the industry, whose importance to the embattled populations as their most important refuge for relaxation and entertainment increased with every battle. If dividends could not consistently be ploughed back in part to improve the product, as actor-managers employed their available funds, then, in the war, charities could surely be benefited through the showing of a single motion picture.

‘At this point I explained my idea to two English friends, Victor Saville and Herbert Wilcox, who cottoned on to it immediately, and agreed to contribute their time and intelligence as one means of repaying the American public for the outpouring of Bundles for Britain and similar acts of friendship towards Britain. To my gratification, the powers at RKO agreed to finance the undertaking.

‘We had enthusiastic meetings with dozens of British actors who pledged themselves to do their all for us. But when the time came to work out details with their agents and fit in with their timetables, we ran into trouble. In the end after Wilcox was compelled to return to England on business, Victor Saville and I were left to push ahead with our plans.

‘The result was Forever and a Day, a patriotic piece of wartime sentiment to which a multitude of people gave their talents. It was shown throughout the free world, the entire proceeds in each country going to a national charity chosen by that country’s head of state. A representative group of us went to Washington to hand a copy of the film to President Roosevelt, who nominated the March of Dimes as the U.S. beneficiary. With Aubrey Smith, I went to Ottawa to present a print to the Governor-General of Canada, the Earl of Athlone.’

Cementing a reputation with Walt Disney

Working for Disney Robert completed 19 films in as many years – including some that remain hugely popular even if Stevenson’s name is not readily associated with them.

Stevenson’s long career with Walt Disney is notable in several ways. The films Robert directed were among the biggest box office successes of the period – in commercial terms he was without equal. He summed up his approach as follows: ‘When I’m directing a picture what I have in mind is a happy audience enjoying it in a movie house.’ Evidently he was a modest man who put the needs of his employer and the cinema-going public before his own name and reputation. This may explain in part why he is not better known today.

Stevenson’s relative anonymity may also reflect a pragmatic approach on his part to working with Disney: ‘Walt would never let any person get in and start building a big team, an empire,’ he said. ‘The tradition here was that if anybody got so important that they put the name on the door, they would not be here in a couple of weeks.’

Also of interest in the possible clash in world views of Disney and Stevenson. Disney was a political and cultural conservative in many ways; Stevenson was notably liberal. Yet the two had a good personal and professional relationship.

For English audiences Mary Poppins, Bedknobs and Broomsticks and The Love Bug remain popular with families; in the States the earlier Johnny Tremain and Old Yeller still have their fans. Stevenson (usually called ‘Bob’ by those that worked closely with him) proved himself over and over again to be a reliable, unfussy professional who relished telling stories and entertaining people. A highly educated man, Stevenson was not pretentious nor was he an elitist. It seemed that he recognised his good fortune to be working with some of the great names in American and British 20th century film history and was happy both to entertain and to make money for his employers.

Johnny Tremain (1957) was his first Disney film and was based on a novel by Esther Forbes. Johnny is a 16-year-old who ends up with a small role in the American revolution against the English. Paul Revere and the Boston Tea Party figure in the story. It would be nice to think that this job was a little joke that Disney was having with his British director. (Although Stevenson became an American citizen he never lost his educated English accent).

In the same year he made Old Yeller – another literary adaptation. Although it stars a boy and his dog the climax of the story is too heart-rending for some young viewers. Not an obvious Christmas film. Here is one on-line discussion of the film: ‘It’s almost impossible to discuss Walt Disney’s Old Yeller without jumping straight into a consideration of the 1957 film’s third act raison d’etre – the death of the eponymous mongrel at the hands of his grief-stricken young owner (Tommy Kirk). Without this tragic turn of events, the story (based on a novel by Texas prairie writer Fred Gipson) would have made passable entertainment and still turned a profit for the Buena Vista Distribution Company without invalidating New York Times critic Bosley Crowther’s assessment of it as “a nice, trim little family picture.” With the inclusion of this unexpected and entirely horrific complication, the tale became legend – perhaps even a generational rite of passage. Stephen King might never have written Cujo had Old Yeller not become infected with rabies while protecting his adopted frontier family from an afflicted gray wolf; one of the best laugh lines in the 1981 military comedy Stripes is when loose cannon non-com Bill Murray rallies the troops with the truth-or-dare question “Who cried when Old Yeller got shot?” The twist in the wagging tail of Old Yeller has in the half century since its release become a pop cultural punch line for such sitcoms as The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air and Friends (in which it is referred to as a “sick doggy snuff film”), while in the syndicated comic strip Garfield, the lasagne-loving, dog-hating fat cat praises the film’s “happy” ending.

‘Love it or hate it, the death of Old Yeller is thematically consistent with Walt Disney product of the post-WWII era, in which traumatic turning points were key to the studio’s aesthetic. Disney’s brand of tough love meant that Bambi [1942] had to see his mother gunned down before his very eyes while Dumbo [1941] was torn from his own mother’s embrace and sold into a kind of slavery and Pinocchio [1940] and his tearaway chums were turned into braying donkeys.’

After two very American subjects Stevenson was given something more nearly British – well Irish, actually, for his next Disney project. Darby O’Gill and the Little People (1959) has every Irish cliché in it; Darby is an old fiddler in search of a pot of gold but he has to outwit a leprechaun. Filmed entirely in California Darby O’Gill remains great fun – and rather overlooked in the Disney catalogue – the special effects are remarkable for the time. It also includes that well-known Irishman Sean Connery who according to one critic is ‘merely tall, dark and handsome.’ Whilst certificated ‘U’ the scene in which a banshee carts Darby off in a chariot of death will unsettle some young viewers!

A respectable version of Kidnapped, based on the novel by Stevenson’s namesake, followed. This time filming took place in the UK – with the exterior shots around Fort William and Glen Coe with the studio work at Pinewood. Peter Finch headed a largely British cast. A couple of years later Stevenson completed another British project In Search of the Castaways which included the likes of Hayley Mills, Wilfred Hyde White, George Sanders and Wilfrid Brambell in the cast. Loosely based on a novel by Jules Verne, the French connection was cemented by Maurice Chevalier who assists two children in the search for their missing father. This was to be the last film Stevenson made in the UK for some years. His mother’s death in 1959 (around the time that Kidnapped was shot) may have meant the end of his emotional connection with Britain.

Either side of Castaways Robert worked with Fred MacMurray on a pair of family-friendly comedies – The Absent Minded Professor (1961) and Son of Flubber (1963). In both MacMurray plays university professor and scientist Ned Brainard. In the first film he invents an anti-gravity substance which allows things to fly. All sorts of fun follows but the ‘story’ hinges on the attempts of a corrupt businessman to take a controlling interest in the professor’s ‘flubber’. It would be pushing it to describe the film as anti-capitalist but it is an example of how Disney’s films do not always carry the message you might expect. Rather, Disney champions the individual, the innovator – people more like himself as he sees it, perhaps. (Robin Williams starred in a remake – Flubber – which made a lot of money but is regarded as a much poorer film than the black-and-white original.)

Both films were big successes at the box office and some of the set pieces remain funny and the visual slapstick elements work well with younger viewers – there is none of the trauma of, for example, Old Yeller.

Stevenson made another pair of comedies for Disney; The Love Bug (1968) and Herbie Rides Again (1974) are thin on plot but have plenty of fun and laughs in them. Herbie is, of course a Volkswagen Beetle car with a mind of his own. The Love Bug was one of the last films that Walt Disney had much involvement in – he died two years before its release but he was very much part of the planning for the film. It cost just over $5m to make but took ten times that amount at the US box office alone. With returns like that it is easy to see why Stevenson remained a favourite with the Studio.

The Love Bug starred Dean Jones and David Tomlinson – both of whom were to work with Robert again. Although Herbie is obviously a VW apparently the German company did not give permission for the use of their logo – this would hardly happen in 2017 one feels! Herbie is numbered ‘53’ for the race scenes – a number worn by a favoured Los Angeles Dodgers baseball player evidently.

Disney capitalised on the success of the film with a string of sequels and TV specials but Stevenson was only involved in the second film, Herbie Rides Again which enjoyed similar commercial success.

Bedknobs and Dinosaurs

Disney died in 1966 but Stevenson continued to work for the studio until his retirement in 1976 (after The Shaggy D.A). For UK audiences two of his better known late films are Bedknobs and Broomsticks (1971) and One of Our Dinosaurs is Missing (1975).

To some extent Bedknobs continued in the style of Mary Poppins. Also based on story by an English author (Mary Norton, author of The Borrowers series) the film too benefited from songs by the Sherman brothers, starred David Tomlinson and combined live action with animation. There was an element of uncertainty about the final shape of the film – whether that is down to the absence of clear direction from the studio chiefs or a lack of confidence on Stevenson’s part is hard to know.

The film exists in several version ranging in length from around 95 minutes to nearly 140 minutes (which was close to the final version of Mary Poppins). In the shorter edits songs are much abbreviated or dropped altogether. Certainly Bedknobs was not the success that Poppins was. The exterior scenes were shot at Corfe Castle, Dorset.

David Tomlinson was born in 1917 and Buxton Film was happy to mark his centenary with a sing-a-long screening of the film which featured his most famous role. He had a long career in film for more than 20 years before he was cast by Disney as George Banks in Mary Poppins. He also worked with Stevenson and Disney in The Love Bug as well as Bedknobs.

Robert’s penultimate film was another ‘English’ one. One of Our Dinosaurs is Missing was made at Elstree and Pinetree Studios with a cast that is very much a ‘who’s who’ of British light entertainment. The film stars Peter Ustinov but includes Derek Nimmo, Helen Hayes, Max Wall, Bernard Bresslaw, Joan Sims, Roy Kinnear and many others. Audiences were underwhelmed, however. Distinguished critic Roger Ebert wrote: ‘You can’t really get stirred up about a movie like this. It’s inoffensive, it’s pleasant enough, Ustinov occasionally gives evidence that he knows he is making a fool of himself and even enjoys it a little, and there are the obligatory small children…’

Perhaps Robert sensed that it would soon be time to retire? For Christmas 1976 Disney released The Shaggy D.A. in which a would-be local politician is turned into a dog by an opponent with magical gifts. It isn’t a great film but it is a respectable finale and at the time the Disney studio was struggling a bit. Its great years were either in the past or some way off in the future. Robert Stevenson was 71, he had been working in film and TV pretty much non-stop for 46 years. He had made some memorable films which entertained millions; he was a diligent professional, a credit to himself and the industry he chose.

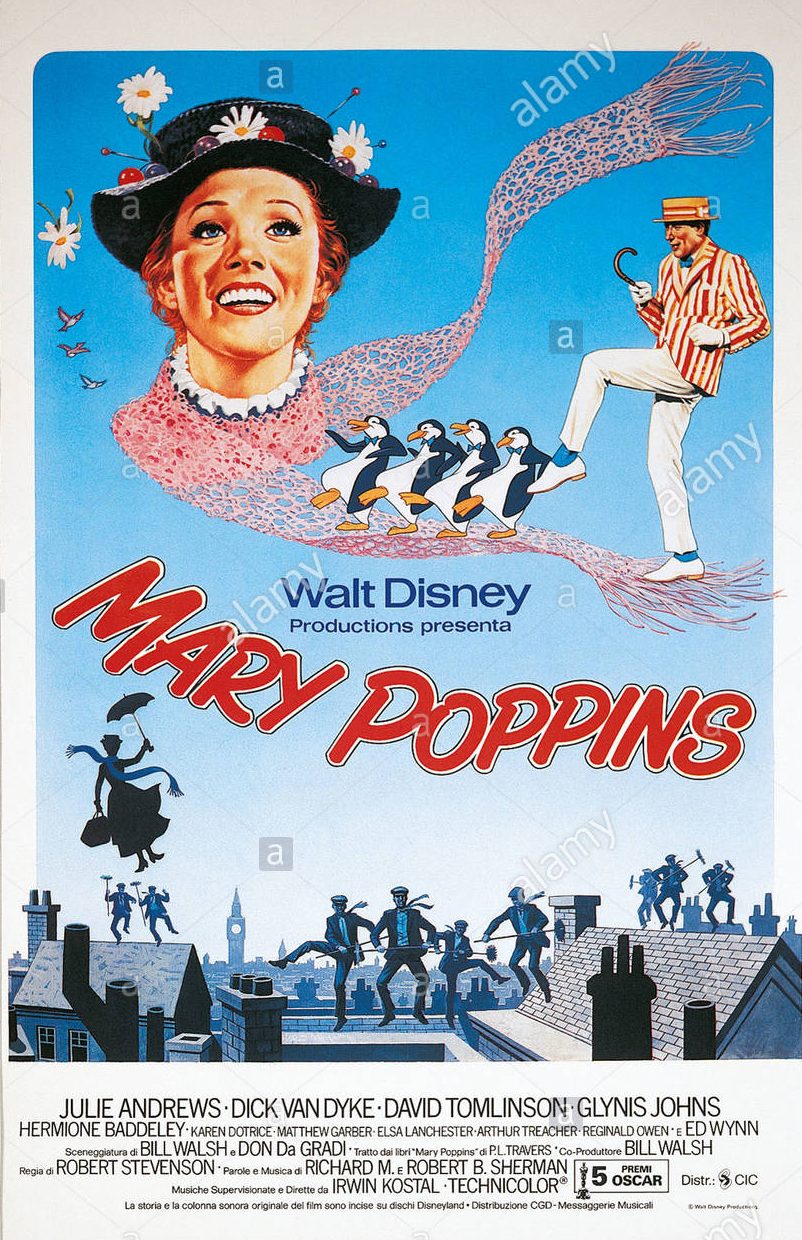

Mary Poppins (1964)

Even if few people connect the name of Robert Stevenson with Mary Poppins it is the best-loved film that he directed. Pamela Lyndon Travers published the first in her series of books about the eponymous nanny in 1934. It was an immediate success and a sequel followed in 1935. The first two books provided the source material for the Disney film. The story is much more complicated than that – and Disney offered a version of it in the excellent film Saving Mr Banks (2013).

PL Travers was reluctant to sell the rights to Disney and negotiations and wooing took place over many years. Disney became aware of the book in the mid-1940s and the studio believed that they got the rights to them as early as 1946. Evidently Travers proved difficult to negotiate with from the very beginning and throughout the film-making process and she did not like the end product. She thought it too sentimental, too sugary and omitted some of the darkness of her own story-telling. She was unhappy that Mary Poppins seemed not to recognise the authority of her employers, Mr and Mrs Banks. She accepted that it was “a good film on its own level” but not true to her vision.

Mary Poppins is another example of Disney producing a story that you might suppose to be out of keeping with some of his own values and

beliefs. Winifred Banks is a suffragette too busy campaigning to care properly for her children – but then the English middle-classes have always had governesses and nannies for that reason. George Banks puts his work first and his family second; his determination to persuade his children to open a bank account leads to a run on the bank and, seemingly, personal disaster. At one level this is a film that is anti-capitalist and which promotes the values of co-operation, playfulness and sides with the poorest.

Disney biographer Neal Gabler suggests that: ‘If his earlier films had spoken to young Walt Disney’s need for empowerment, Poppins spoke to the older Walt Disney’s predicament as a corporate captain burdened with duties, and he could certainly identify both with Mr Banks, the stodgy banker who has a child lurking within him, and with Mary Poppins, the magical nanny who manages to emancipate that child. The film embodied his new vicarious dream of shirking responsibilities he knew he really couldn’t shirk, of being the child that reporters often said he was but that he couldn’t really be.’

The film was nominated for 13 Oscars (including one for director Stevenson) and won five – including Best Actress (Julie Andrews) and Best Original Song (“Chim Chim Cher-ee”). By all reports the film gave much pleasure to the cast and crew that made it and Disney, himself, was delighted finally to be working on a project that he had set his heart on years previously.

Robert Stevenson died on 30 April, 1986, at his home in Santa Barbara, California. He was 81 and had been ill for some time.

Keith Savage – April 2017